The residence at 30 Bayles Street was The Lord Mayor’s home built in 1888.

‘During World War ll, while on leave and camped in Royal Park, some servicemen visited/frequented 30 Bayles Street, Parkville, then an illegal brothel.’

Later it became a boarding house and was purchased subsequently by The Archdiocese of Melbourne in 1957.

Now extended and restored to its Victorian magnificence, it is a great place for a party.

Our Parish and Patron

The area of this Parish was originally within the boundaries of St. Mary’s Parish, West Melbourne. The Church was built as a Chapel-of-ease of St Mary’s.

The site of the Church was previously occupied by stone masons making headstones for the Melbourne General Cemetery. Mr Jaguers gave the land for the Church.

The foundation stone was blessed and laid by the then Archbishop of Melbourne, Dr. Daniel Mannix on the 14th October, 1934, under the patronage of St Carthage.

The building was completed in 1935 and the area of Parkville remained part of the Parish of St Mary’s for the next 22 years. In November 1956, the new Parish of St. Carthage, Parkville was established independently of West Melbourne.

St Carthage is the patron of saint of Lismore, County Waterford in Ireland. He is known for his great reverence for the House of God and was responsible for the building of several famous schools and monasteries. St Carthage spent much of his life in instruction,by preaching and example, of those who came to him.

St Carthage is the patron of saint of Lismore, County Waterford in Ireland. He is known for his great reverence for the House of God and was responsible for the building of several famous schools and monasteries. St Carthage spent much of his life in instruction,by preaching and example, of those who came to him.

He was born in County Kerry near Castlemaine in 564. While still a young boy herding pigs, he was drawn to follow St Carthage the senior and his monks, who passed by him chanting the Psalms. He was passed into the care of the older Saint, Bishop of Castlemaine, to be educated, and was eventually ordained a Priest. He followed the monastic discipline of solitude, fasting, prayer and study. He died in the monastery at Lismore after giving a blessing to his monks and students, on the 14 May, 637 (f.d)

A Forgotten Irish Saint, and his Many Churches

(This entry was posted on April 6, 2014 by Tintean Editorial Team/fdg, in Features, History and tagged Carthach, churches, Lismore Australia, Lismore Ireland, Mochuda, Parkville, st. Carthage, Toowoomba. Bookmark the permalink. 3 Comments)

A Feature by Chris Watson

Many Australia’s Catholic churches are dedicated to well-known Irish saints and reflect Catholic devotional ties at the time of the church’s dedication. Churches dedicated to lesser known patron saints, however, also offer a fascinating window into the influence these little known saints had on early Australian Catholicism.

Little is known of Saint Carthage – not even in Ireland – yet there are numerous churches named after him around Australia and and at least one in New Zealand. St Carthage is also known as Mochuda (spellings vary), particularly in Irish language sources. The Irish ‘Carthach’ became the Latin ‘Carthagus’ in written documents, and so, in English, ‘Carthage’

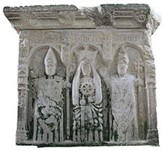

St. Carthage, on left, alongside St. Catherine and St. Patrick, in the Lismore (Church of Ireland) cathedral of St. Carthage. Photo by Andreas F. Borchert

He was born near Castlemaine, Co Kerry, around 564 and became a monk after hearing the chanting of monks while he tended his father’s swine. He became the leader of a flourishing monastery at Rahan in Co Meath, in the Irish midlands. He was especially renowned for his care for lepers.

Because of jealous abbots and local rulers, he was forced, as an old man, to go south to Lismore in Co Waterford with other monks in his community. The lepers, already in effect refugees from their own kin, were forced to move with him. His monastery there became a famous centre of learning. The Church of Ireland and the Catholic Church both have churches dedicated to him in Lismore, Ireland.

The earliest definite date I have found for a St Carthage church in Australia is at Lismore, NSW. Jeremiah Doyle, a young priest recruited to the Armidale diocese, had the name of its small church changed from St Mary’s in 1880. Doyle had studied at the Cistercian Mount Melleray Abbey, near Lismore, before going to All Hallows in Dublin, and thence to Australia. Mount Melleray appears often in the story of the priests associated with Carthage churches in Australasia. Doyle was made the first bishop of the new diocese of Grafton, which he successfully lobbied the Pope to change to the Diocese of Lismore in 1900. Although this town’s name originally came from a Scottish Lismore, Doyle took the opportunity to give St Carthage a Catholic Cathedral in Lismore in Australia, something he had not had at Lismore in Ireland for many centuries: the Catholic church in Lismore was erected between 1881-1884. The Church of Ireland cathedral has the old site.

Catholic parish church, Lismore, Ireland.

Catholic parish church, Lismore, Ireland.

The church at Cabarlah near Toowoomba had its name changed from St Patrick’s to St. Carthage’s in the early 1890s. This change is probably associated with Robert Dunne, who grew up in Lismore, and walked to midnight mass at Mount Melleray with his father on Christmas Eve 1841. He made a retreat there before his first communion. He was in charge of the parish Toowoomba parish from 1868 to 1880, and was at Mount Melleray, considering joining the community when appointed Bishop of Brisbane in 1882.

Allansford, in the Western District of Victoria, has a St Carthage church which celebrated its centenary in 1990. Its founding doesn’t follow the Lismore Waterford/Mount Melleray pattern, in that its founder was not from Lismore or Mount Melleray, the ‘local’ monastery for Lismore. Msgr John O’Dowd, priest in charge of the Warrnambool parish, came from Castlemaine, Co Kerry. There is now a St Carthage Catholic Church and Church of Ireland, at Kiltallagh, St Carthage’s birthplace. The Catholic church in Kiltallagh was built about two years after the Allansford one. The Allansford church’s centenary booklet indicates a proud and active history, but makes no reference to the saint who gave the church its name.

St Carthage came to the suburbs in 1929 at Gordon Park, then a new estate on the outskirts of Brisbane. Laying the foundation stone for the Church and school, Archbishop Duhig referred to Carthage as ‘one of the best-known saints of Ireland’s golden age.’ This seems a little exaggerated. But it is the earliest reference I know to the saint other than a name that reflects the personal devotion and perhaps nostalgia of a founding priest from the south of Ireland.Information about St Carthage is thin if non-existent in the antipodes. For example, in the press report of the dedication of St Carthage’s Church in Waikaka (New Zealand) in 1906, there is not a word about the patron saint himself in the celebratory speeches. But the parish priest of the Waikaka church, Father Patrick O’Donnell had also studied at Mount Mellerey. The inspiration for the name for the Church at Gordon Park came from Fr John McCarthy. His request to a monk at Mount Melleray for information about the saint, led to the publication in Ireland of the biography of St Carthage in 1937. The Australian edition has a preface by James Duhig, the typescript of which is in the Brisbane Archdiocesan files for Gordon Park. A newer church at Gordon Park on the site is still in use.

The latest of the Carthage churches is at Parkville, Victoria. It was established as a chapel of ease for St Mary’s, Star of the Sea, West Melbourne, at the urging of John Norris, also educated at Mount Melleray. Speakers at the laying of the Foundation stone in 1934 included Daniel Mannix and Jeremiah Murphy SJ, Rector of Newman College, who stressed the aptness of a location opposite the University of Melbourne, commenting:

It was a happy thought on the part of Fr Norris to choose as patron of the new church such a distinguished man as St Carthage, who was virtually the founder of a kind of small university.

St Carthage’s, Parkville became a separate parish in 1956.

St Carthage and St. Therese of Lisieux, St. Carthage’s Parkville Victoria

St Carthage and St. Therese of Lisieux, St. Carthage’s Parkville Victoria

St Carthage now had, as far as I know, his first stained glass window in an Australian church. (He also has a stained glass window in St. Philomena’s chapel at the Mount Mellerey Monastery.) The pairing of his window with one of St Thérèse of Lisieux, (the patron saint of Australia and of missionaries), suggests an emphasis on him as a model for the Irish Catholic spirituality of the thirties, especially given the wording of the scroll that he holds: ‘Here shall be my rest, for I have chosen it.’ The monk, driven from home sees his place of exile as his own choice. This quote also reminds Irish emigrants (such as Norris himself) and their descendants that while they might honour their Irish ancestry, Australia is now their home. Maybe he could be thought of as the Irish patron saint of refugees?

Further background information: Sources

CHRIS WATSON. Since retiring as Lecturer in English at LaTrobe University, Chris Watson has followed interests in Irish language, literature and history.

The relics in the altar of St Carthage’s Parkville

Traditionally, altars in catholic churches contain relics of one or more saints, especially those martyred for their faith. Tthere are relics of four saints preserved in our altar, carved from Carrera marble, which originally belonged to the convent of the Sisters of the Good Shepherd at St James’s Church, Oakleigh, but was transferred to our Parkville church, in cut-down form, in 1967 after their church had to close. According to the booklet produced for the consecration of our church in 1986 by Archbishop Frank Little, the altar contains the relics of four saints. One of these is a relatively recent martyr, St Redemptus, a discalced Carmelite lay brother from Portugal, originally called Thomas Rodriguez da Cunha. He was a missionary killed in 1638 in Aceh now part of Indonesia. Another is St Simplicius, one of a group of Christians martyred in 302 in the time of Diocletian, whose remains (along with fourth-century inscriptions) were rediscovered in Rome in 1868, and taken to Santa Maria Maggiore. The third is a relic reportedly of Blandina, a fifteen-year old slave girl, Blandina, whose martyrdom in Lyons, France in the year 177, is described in a letter preserved by the fourth-century historian, Eusebius. It reports that she was one of several martyrs, thrown to wild animals in the Roman amphitheatre. The letter seems to give an eye-witness report of the martyrdom of various Christians at Lyons. Nothing is known of the fourth saint, a certain Aelidorus. Some of the relics may have come to St Carthage’s when the altar was brought from Oakleigh to Parkville, in 1967, when Fr Eric D’Arcy was parish priest of St Carthage’s. The relics provide a point of contact with heroic individuals who gave their life to follow Jesus.

Constant Mews.